A Walk Around Tokyo/Edo

/As explained in our website, the Freedom of the Streets project consists of 4 main sub-projects: Edo, Amsterdam, Urban Nature and An Eurasian Perspective. Although the latter three have been in the works for some time, October marked the official kick-start point of the Edo project. So all of the team members flew to Tokyo to participate in two academic events, and also to collect research materials across a number of archives. But the first day was devoted to a short walk across the northeast and southwest parts of Tokyo, through which our team members were able to directly experience some of the topographical peculiarities of the city, and to discuss the changes between Edo and Tokyo while walking and enjoying the scenery.

In fact, we are far from the only ones interested in this kind of exploration. For a number of years, there has been a small trend among Tokyoites to engage in what we may call "historical experience walks". Armed with books that compare old maps and images of Edo with current maps, these history fans roam the streets of the city (especially during the early morning), stopping at historical landmarks and imagining the tales of successful (or failed) samurai rebellions, suicide pacts among lovers who could not overcome the social restrictions of their time, famous actors walking through beautiful gardens, or reimagining the former splendor of rivers that have been buried for decades and are now converted into busy roads as a result of the rapid post-war modernization process. There are even a few semi-famous programs on Japanese TV, in which actors or TV hosts leisurely walk across cities, parks and temples with a local guide, unraveling the fascinating stories that took place. Of these, my personal favorite is by far the program "Bura Tamori" by NHK Japan (and internationally on NHK World Premium), in which a widely-known TV and radio star known as Tamori walks through cities and natural parks all over Japan accompanied by historians and lecturers from various local universities, who one by one explain the urban evolution of each city, the roles of topography, geology, geography and culture in determining urban form, and the unique identities of each site. Please do check it out if you ever have the chance, and especially if you are passionate lovers of urban history.

But returning to our project, on October 27 the entire team was finally reunited in Tokyo, and despite the jet-lagged looks on their faces, we were able to walk around Ueno Park (especially the surroundings of the Shinobazu Pond), Bunkyo-ku (in which the campus of the University of Tokyo is located) and Roppongi (especially the Mori Tower district).

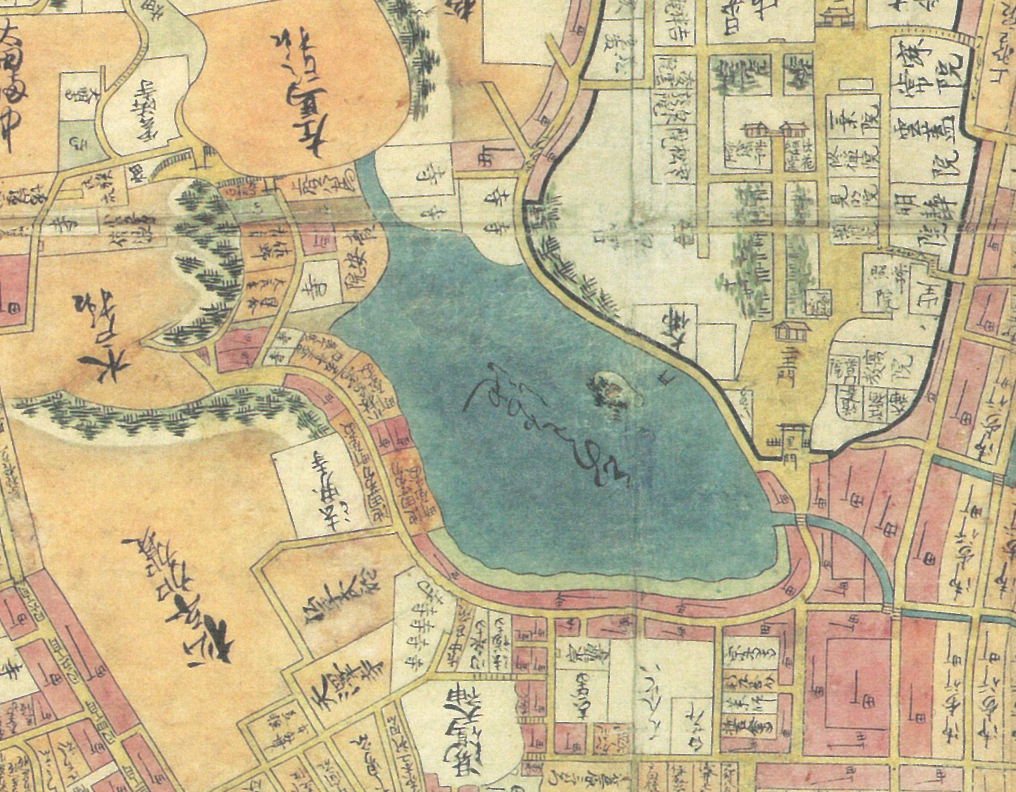

The Shinobazu Pond, located on the west side of the Ueno district, is an especially important site not just in Tokyo, but even during the Edo period, as it attracted crowds of urban dwellers coming to enjoy its flowers or appreciate its cherry blossom trees. This was originally a natural pond that was artificially expanded through the centuries, and even completely drained at one point. For most of the Edo period, Ueno and this pond were located close to the northeast limits of the city. It had a number of temples, of which the most picturesque is the Benten-dō temple (弁天堂) situated in a small island within the Shinobazu lake. For a long time, the only way to access the Benten island (which held the temple Kan'ei-ji during the Edo period) was by boat (later, a narrow passage in its east side was built), but currently a number of landfilled paths allow us to walk through the middle of the pond, and to appreciate its beauty from up-close (see the two maps below).

Left/Right: The Shinobazu Pond in its current situation (Sources: Google Maps / Wikipedia).

Left: Shinobazu Pond in the Meireki period map of Edo (明暦大江戸図), around 1655-1658.

Right: the same pond in a late Edo period map (御江戸大絵図) held by Kagoshima University Library.

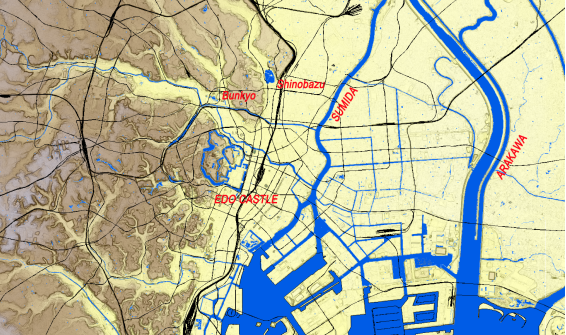

This area is also notable because it marks the intermediate point between the very shallow deltas of the Sumida and Arakawa rivers in the east limit of Tokyo, and the hilly region of Bunkyo-ku. Nobility and prestigious families would usually locate themselves in the higher lands such as Bunkyo-ku, due to their safe location against tsunamis. On the other hand, the intermediate region of Ueno was mostly occupied by commoners and merchants, and as we reach the shallower lands near the river, we would see more and more people of lower status and with less resources, as well as fishermen settlements who needed to have quick access to the sea (In fact, the way in which topography influences the distribution of social classes can also be seen in other early modern cities such as Nagasaki, which had people of poorer status along the margins of the Nakashima River and richer people in the upper cape).

Topographical map of contemporary Tokyo, based on GIS data.

Even today, the area of Ueno is still marked in risk-management materials as a risk zone in the case of tsunamis. Even though it is now located about 2-3 km away from the Sumida River (because the city gradually landfilled more and more of its coastline), there is still a small possibility that in the case of a massive earthquake such as the one that victimized the Tohoku region in 2011, a large tsunami wave could conceivably reach inland as far as the foothill of the Bunkyo-ku area. So in the case of a tsunami warning, people would be advised to climb the Bunkyo-ku hill, or the small elevated area that is now known as the Ueno Park.

Having left Ueno, we took the Hibiya subway line to directly reach Roppongi station in the southwest part of Tokyo. After a brief walk around the area, we went up to the famous Mori Tower to experience its City View Sky Deck. It is the highest place in Tokyo where you can access the rooftop, without anything to block you from wind and rain. During days of bad weather, the Sky Deck is not accessible, but during a normal day the view is simply breathtaking. We arrived just in time to see the sunset, as it fell over the Japanese Alps region, not far from the world-famous Fuji Mountain. The time from late October onwards is especially good for viewing Mount Fuji from Tokyo, since during the morning and sunset times, moisture levels decrease considerably, and it becomes possible to see much further than during the spring and summer seasons.

And so, while enjoying the sunset, we studied the geographical boundaries of Edo from our excellent vantage point: we saw Atago hill near Shinagawa, which was a popular place from which to view the city of Edo; then on the West there was Shinjuku park, on the South the 30-year old landfilled entertainment district of Odaiba, which in the late Edo period was a group of isolated islands containing cannons and military fortifications; and in the East we saw all the way to Asakusa and Oshigome, where the Sky Tree, the tallest building in Japan, is located.

Finally, we went down to enjoy a sushi dinner in the Roppongi district, passing through the myriads of foreigners looking to enjoy its many dance clubs and pubs, and finally returned to our hotel for a well-deserved rest! Please stay tuned for future posts concerning our recent activities.